Simplicity Wins: Command Context Consistency

How Self-Contained Features and Event Logs Replace Legacy Models

How can you deliver features from day one without running into the trap of a bad architecture?

That’s the question I asked myself for years. And for years, I was on the wrong path, following object-oriented paradigms and object models that simulated the real world, and doing lots of upfront design. It always felt like preparing for something that never really came.

The real change began when I came across Jimmy Bogard's Vertical Slice Architecture. His approach remained within the realm of object-oriented programming, with layered logic encapsulated within feature folders. However, he described something different that made me think more deeply. Code shaped like a request, followed by 'do something', followed by a response. That stuck. It aligned with the concept of separating commands and queries. It showed me a direction worth exploring.

The more I researched, the clearer it became that what we have been taught for decades is ineffective. These legacy architecture approaches are not just slightly outdated; they are completely incompatible with the way real systems grow. They assume that you know everything from the outset. They rely on a central, single model what Domain-Driven Design refers to as 'Bounded Contexts'. They expect the domain to be captured in objects before you’ve even had your first real conversation with your users.

And they fall apart the moment change arrives.

What's Broken in Legacy Architectures

Most legacy architectures, such as Clean Architecture, Uncle Bobs Onion approach, the Hexagonal Architecture and any kind of horizontal layered approaches, all share the same hidden flaw.

They assume there is a single, central model of truth.

They also require you to define that model at the outset.

This leads to lengthy design phases. Endless domain discussions. Abstract object hierarchies. Weeks are lost modelling entities and aggregates before a single useful feature is delivered.

The problem is simple: these models do not reflect how software actually evolves.

You think you're building a universal structure. But every new story brings surprises. Developers sit with domain experts and discover rules that nobody had mentioned before. Or contradictions. They also encounter real-world chaos that doesn’t fit the model. So the model is patched up. Workarounds increase. The design becomes fragile, not because of poor coding, but because of flawed assumptions.

Even good ideas such as CQRS and Event Sourcing can fall into this trap.

When Greg Young introduced them, his intention was to escape the rigid model. However, DDD and aggregates came along for the ride. Suddenly, people were spending weeks trying to define the 'right' aggregate boundaries, once again resorting to central modelling under a new label.

It's unnecessary, it's not agile, and it's not how real systems succeed.

A Different Mindset: Simplicity, Not Structure Worship

Here’s the shift:

You don't need a single model.

You don't need aggregates either.

You don't need an upfront design.

What you need is a mindset that builds from the bottom up: feature by feature, fact by fact. Each feature is self-contained. It knows just what it needs to know. It doesn’t depend on a centralized object model. It doesn’t share fragile abstractions with other features. It focuses on one job and does it well.

The secret is this:

You don’t model objects, you record facts.

When a command (intent) comes in, it either produces new facts (events) or not.

You take in data, apply business rules, and emit events. That’s it.

You don’t need to know how the system will use those events later.

You just capture what happened.

These events are stored in an append-only log. That log is the truth of the domain. It’s the raw, immutable material of your system. You never go back and rewrite it. You just keep adding facts.

And to be clear:

I am not advocating for an unstructured mess of data and code. That's not my goal.

My goal is to get rid of unnecessary complexity and data structures in the right place. The goal is to build robust systems with simplicity that has boundaries.

Commands Act in Context

A command does not update an object. It does not load a parcel from the database. And, is does not rehydrate an aggregate or mutate anything. It simply looks at the facts (the relevant events that happened before), and decides what to do.

That’s the point. Each command runs in its own local context. It knows exactly what it needs. It is independent of the global state and does not share mutable objects. It takes the input, checks the facts, applies the rules, and appends the new events to the log.

But, let's take a real example from the logistics domain.

Delivery Attempt Tracking

Failed parcel deliveries happen every day. We want to track them and decide what to do when too many attempts fail. The rule is simple: after three failed delivery attempts, the parcel should be marked as undeliverable.

There is no object called 'Parcel' here. We don't simulate its state. We simply record what happened.

The command looks like this:

type AttemptDelivery = {

type: "AttemptDelivery";

parcelId: string;

};

In order to make the right decision, we rebuild just enough state for this specific context. We check how many attempts have been made and whether the parcel has been delivered or marked as undeliverable. This is the only information that the feature requires.

function decide(events: EventRecord[], command: AttemptDelivery): DeliveryAttemptResult {

const attempts = events.filter(e => e.eventType === "DeliveryAttempted").length;

const alreadyDelivered = events.some(e => e.eventType === "DeliverySucceeded");

const undeliverable = events.some(e => e.eventType === "DeliveryMarkedUndeliverable");

if (alreadyDelivered) {

return {

success: false,

error: { type: 'ParcelAlreadyDelivered', message: 'Parcel has already been delivered.' }

};

}

if (undeliverable) {

return {

success: false,

error: { type: 'ParcelUndeliverable', message: 'Parcel was already marked as undeliverable.' }

};

}

if (attempts >= 3) {

return {

success: true,

event: {

eventType: "DeliveryMarkedUndeliverable",

payload: { parcelId: command.parcelId }

}

};

}

return {

success: true,

event: {

eventType: "DeliveryAttempted",

payload: { parcelId: command.parcelId }

}

};

}This function does not check database records. It doesn't deal with side effects. It's deterministic: the same input produces the same output. You always know exactly what it does. It’s easy to test and difficult to break.

This is what writing business logic in a functional style means. There is no simulation of real-world objects. There are no hidden state transitions in opaque objects. Just clear, fact-based decisions. Each feature defines its own rules based on the facts relevant to its function. If something changes, it’s easy to update the relevant rules without worrying about breaking other parts of the system. If something is completely irrelevant, rewrite it.

Functional Thinking

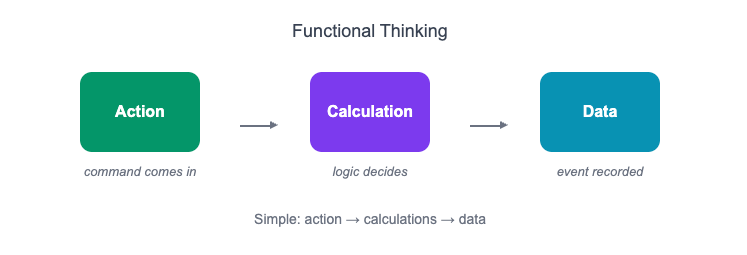

When I say that all these legacy architectural styles do not match, I mean exactly that. They’re all built around the idea of modeling life-cycles and simulating the real world with objects. But that’s not how real systems behave. Real systems respond to intent. Something happens. Rules apply. A decision is made. That’s it.

I found the answer in functional thinking. The model I follow is simple: action, calculations, data. A command comes in, the logic decides what should happen, and a new event is recorded. There is no need for objects that try to hold state. There is no need for aggregates or base classes or factories.

I know, I know... of course technical dependencies still exist. We still need to store events, call external APIs and handle inputs. This is where the idea of separating a functional core from an imperative shell comes in useful. The functional core is where the rules reside. It's pure. It doesn't deal with side effects. It takes input and returns a result. That’s what makes it testable without mocks, and deterministic by design. The shell wraps around it and handles the messy stuff, reading facts from the event store, validating the request, calling APIs, and persisting the result. This way, the logic stays clean and focused, while the technical noise stays on the outside.

I chose this model because it aligns with my approach to building software. I don't want centralized entities where everything depends on everything else. I also don't want to solve this problem using Dependency Inversion (DIP) via indirect methods, because functional dependencies would still remain. I don't want a shared object model that forces teams to agree on the contents of a 'Parcel' or 'Device'.

I want fully self-contained feature slices.

I want to build something that does its job without worrying about the rest of the system. This approach gives me exactly that.

The only thing shared across the system is the event log: the raw, immutable sequence of facts. Every feature can read from it. Every feature can write to it. But what happens inside the slice is completely under its own control.

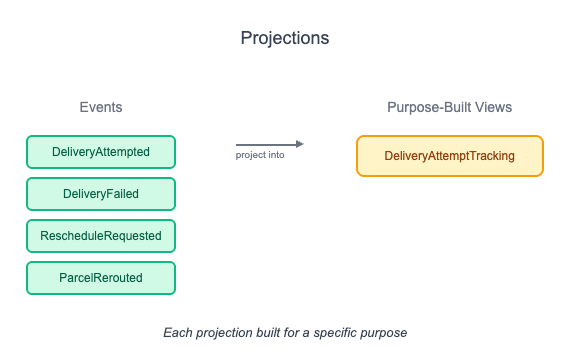

What About Reading?

Reading data follows the same principle.

No shared object model.

No generic repository.

No central read layer that tries to cover every case.

Just views built for a specific purpose, shaped by the needs of a single feature.

Each read model is a projection. It’s built from facts that were already recorded. When something happens in the system, the projection updates. And if nothing relevant happened, it stays the same. That’s how it works.

This projection can be a database table like device_list, failed_deliveries, or driver_route_overview. In other cases, it’s an in-memory view or a pre-computed JSON blob. It doesn't matter. The important part is that it exists only for one use case. It’s not trying to be universal. It doesn't aim to reflect 'the truth' in general. It only reflects enough truth to answer one question quickly.

This means the query side stays decoupled from the write side. You don't need to model your data upfront just to answer future questions. You can always add new projections later, even after the system is in production. That's the power of using facts instead of states. The facts don’t go away. You can reprocess them anytime and shape them into any form you need.

This also means features like AttemptDelivery or MarkAsDelivered don’t have to care about how someone will present these facts later. They just record what happened. The way this information gets displayed or analyzed can evolve later; separately, and without needing to change the feature logic that produced the events.

Build Systems That Flow

Common architectures based on object-oriented thinking try to freeze the world into objects and layers. They assume structure is more important than flow. But the real world does not work like that. Things happen. People change their minds. Requirements evolve. That's why upfront models break. That's why centralized entities collapse under the weight of change.

What works instead is a system that flows with intent and reacts to facts. A system where each feature lives on its own, sees what it needs, and makes decisions without asking permission from the rest of the codebase. A system that grows without becoming fragile.

This isn't about patterns. It's not about buzzwords. It's about creating software that's straightforward, clear, and designed for change. From day one.

Cheers!